|

|

£16.00 |

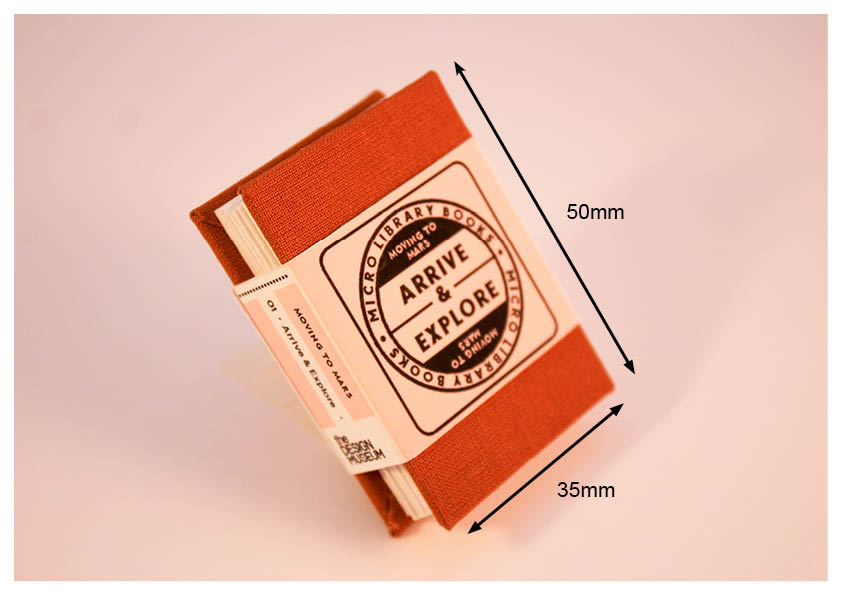

Product details for Arrive & Explore:

Printed by Martel Colour Print

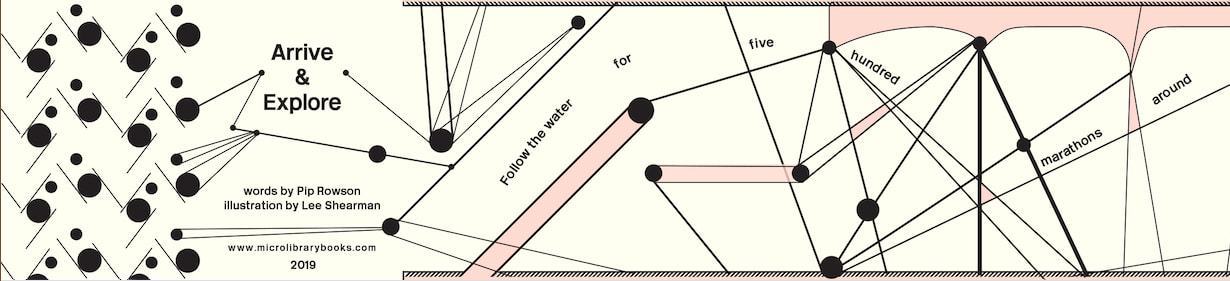

- A beautiful handmade illustrated poetry book created to coincide with the Moving to Mars exhibition.

- Featuring new illustration and design by artist Lee Shearman and poetry by writer Pip Rowson.

- Each copy is giclee printed on 180gsm Xativa paper then concertina-folded by hand. The books are hardbound with card covers and Chocolate-coloured rayon book cloth and finished with a giclee printed belly-band.

- Dimensions: 35mm x 50mm x 14mm (closed) 35 x 50 x 1088mm (unfurled)

- Materials: Giclee print on 180 gsm Xativa paper with rayon and card hardbound covers.

Printed by Martel Colour Print

Map-Making

Before setting out on a journey and to have our intended destination in our sights, we humans are likely, sensibly, to reach for a map. But the landscape of Mars throws up many tensions: it is known and unknown, it is homogenous - the red planet - and incredibly, beautifully, varied. The challenge of mapping the surface of Mars, gives a legacy of imperfect assertions of the planet’s landscape. This is evident in the evolution of the maps of Mars’s canals, for example, which move from Schiaparelli’s 1877 maps to Perrotin and Thollon’s re-rendering in 1886 to Lowell’s 1895 canal map featured in his book Mars, all before today’s state of the art photography and use of robots helped us more accurately understand the planet’s terrain.

In the same way, our earthly language stops short of being able to succinctly describe the discoveries of the Martian terrain. “The names we’ll give to the canals and mountains and cities will fall like so much water on the back of a mallard. No matter how we touch Mars, we’ll never touch it.” (from history of the future by Christophe Canto and Odile Faliu). The words we use for planet Earth’s geography: valleys, canals, plains, deserts, lakes are so intertwined with our own world’s identity that Mars demands new coinage of terms and even that poses a challenge as over the years, the names given to its craters, for example, have had to be crudely recycled due to the sheer number of new discoveries.

Further reading:

Mars After Lowell's Glober by Emmy Ingeborg Brun

Before setting out on a journey and to have our intended destination in our sights, we humans are likely, sensibly, to reach for a map. But the landscape of Mars throws up many tensions: it is known and unknown, it is homogenous - the red planet - and incredibly, beautifully, varied. The challenge of mapping the surface of Mars, gives a legacy of imperfect assertions of the planet’s landscape. This is evident in the evolution of the maps of Mars’s canals, for example, which move from Schiaparelli’s 1877 maps to Perrotin and Thollon’s re-rendering in 1886 to Lowell’s 1895 canal map featured in his book Mars, all before today’s state of the art photography and use of robots helped us more accurately understand the planet’s terrain.

In the same way, our earthly language stops short of being able to succinctly describe the discoveries of the Martian terrain. “The names we’ll give to the canals and mountains and cities will fall like so much water on the back of a mallard. No matter how we touch Mars, we’ll never touch it.” (from history of the future by Christophe Canto and Odile Faliu). The words we use for planet Earth’s geography: valleys, canals, plains, deserts, lakes are so intertwined with our own world’s identity that Mars demands new coinage of terms and even that poses a challenge as over the years, the names given to its craters, for example, have had to be crudely recycled due to the sheer number of new discoveries.

Further reading:

Mars After Lowell's Glober by Emmy Ingeborg Brun